Frances Glessner Lee took forensic science to a new level by recreating violent crime scenes. Not only that, she also became America’s first female police officer.

Frances Glessner Lee took forensic science to a new level by recreating violent crime scenes. Not only that, she also became America’s first female police officer.

When passion is limited by time

Frances Glessner Lee (1878-1962), who is known as the “godmother of forensic science” , was 𝐛𝐨𝐫𝐧 into a wealthy family in Chicago and thus, she inherited a huge fortune from her father. my mom.

From 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥hood, Lee and his brother were taught at home by tutors. When they both grew up, Lee wanted to study medicine. However, Lee’s father did not allow his daughter to continue her education, because at that time, “a lady who did not go to school ” was the correct view.

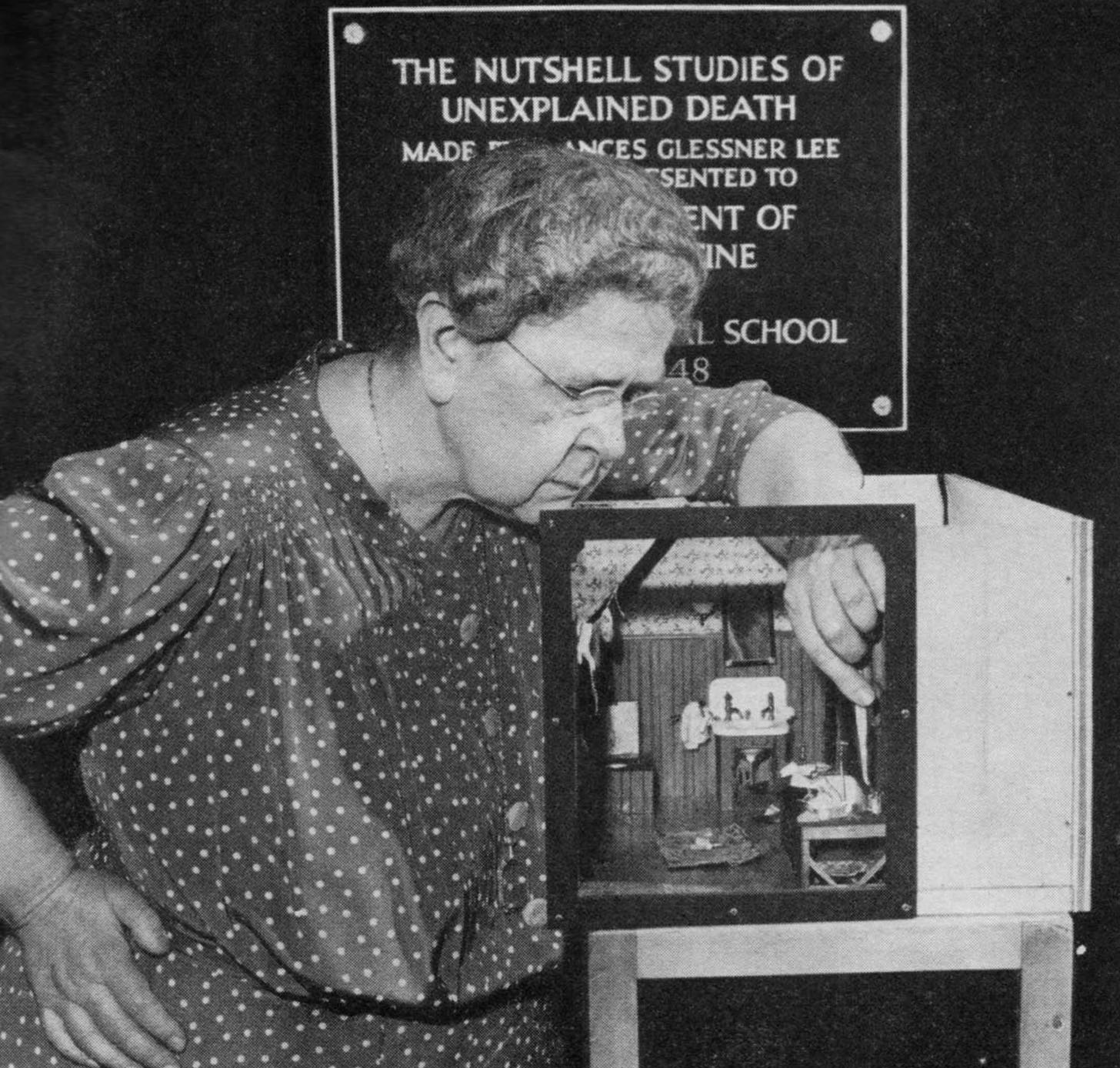

Frances Glessner Lee while researching case models in the early 1940s.

When he was just 19 years old, Lee married a lawyer and they had three 𝘤𝘩𝘪𝘭𝘥ren together, but this marriage did not come to an end because they both decided to divorce after many years of living together. In the 1930s, after a divorce and at the age of 50, Lee inherited the family fortune.

Journey to pursue your dream

As a young man, Lee enjoyed stories about Sherlock Holmes. But it was her brother’s classmate at Harvard, George Burgess Magrath, who really sparked Lee’s passion for crime scene investigation and forensics.

Magrath was studying medicine at the time, and often told Lee stories about real-life crimes he helped solve. This sparked Lee’s fascination with science, or more specifically, forensic medicine. Magrath later became a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School and chief medical examiner in Boston.

The works of Frances Glessner Lee are meticulously made to the smallest detail.

In Death in Diorama – Frances Glessner Lee’s biography – it is written: “Through her friendship with Magrath, she learned the challenges of investigating the cause of violent death.” In fact, the staff Medical degrees are often not required for investigation, and police are not trained in how to collect and preserve medical evidence, so many murderers have been let free because of this shortcoming.

Greatly inspired, Lee then decided to pursue his passion – forensic investigation . In 1931, Lee donated $250,000 to establish the country’s first Department of Legal Medicine at Harvard University, and nominated George Magrath as president.

Because the forensic field during this period was dominated by men, Lee had to find a way to stand out among them and break into the small field.

A unique but somewhat scary idea popped into her mind: Create small replicas of real crime scenes to help detectives look for clues in horrifying cases, innocent deaths, and crime scenes. clear reason.

However, the construction of this crime scene was not carried out on real people, but by Lee on doll houses . Making miniature models is a popular hobby among wealthy women. So Lee took what she knew and got to work.

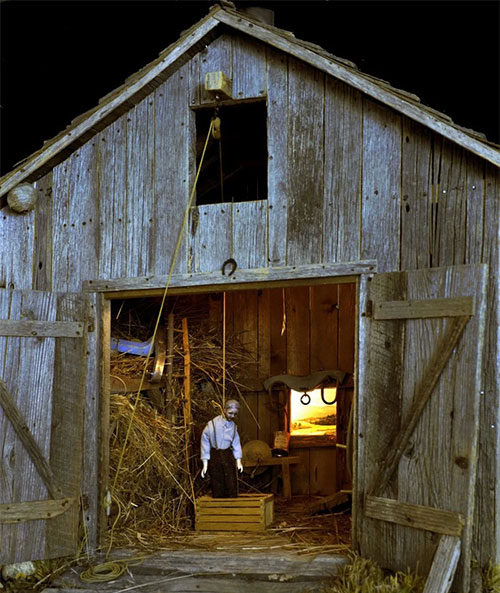

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Lee used actual police cases and recreated grisly crime scenes as miniature models. The details in Lee’s work are remarkable – everything from the placement of rotting bodies to the deep red bloodstains on the patterned wallpaper.

This series of simulations was called The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death , and Lee created a total of 19 of them. These models were later used to train investigators, helping them “convict the guilty, acquit the innocent, and find the truth in a concise manner.”

Lee knew that to be taken seriously, her “crime scenes” needed to not only be meticulously crafted, but also scientifically accurate. She bought doll heads and parts made of porcelain, but always made sure their shape matched the biological structure of the human body.

“You can’t buy a doll with cadaveric spasticity ,” said Ariel O’Connor, a conservator at the Smithsonian . In his series of simulations, Lee recreated the cases with astonishing detail: A woman was hanging in an unusually stiff neck position – a sign that she may have died before being caught. hanged, the dolls were pale in color while some body parts were burgundy – evidence suggesting whether the body had been moved.

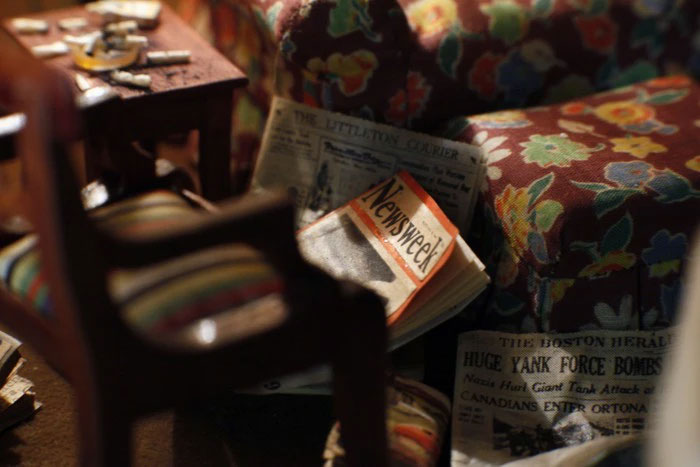

At work, Lee is difficult to the point of being obsessive. One of her mockumentary works, titled “Saloon and Jail ,” depicts a man lying face down on the street. Debris littered the sidewalk: Miniature cigarettes, banana peels, scraps of paper with someone’s face drawn on them. The storefront at the back displays real-cover newspapers and magazines from the day the man died. A bin of tiny, colorful lollipops sits under the magazines, each candy individually wrapped in cellophane. All the details are crafted to the point of not being more meticulous.

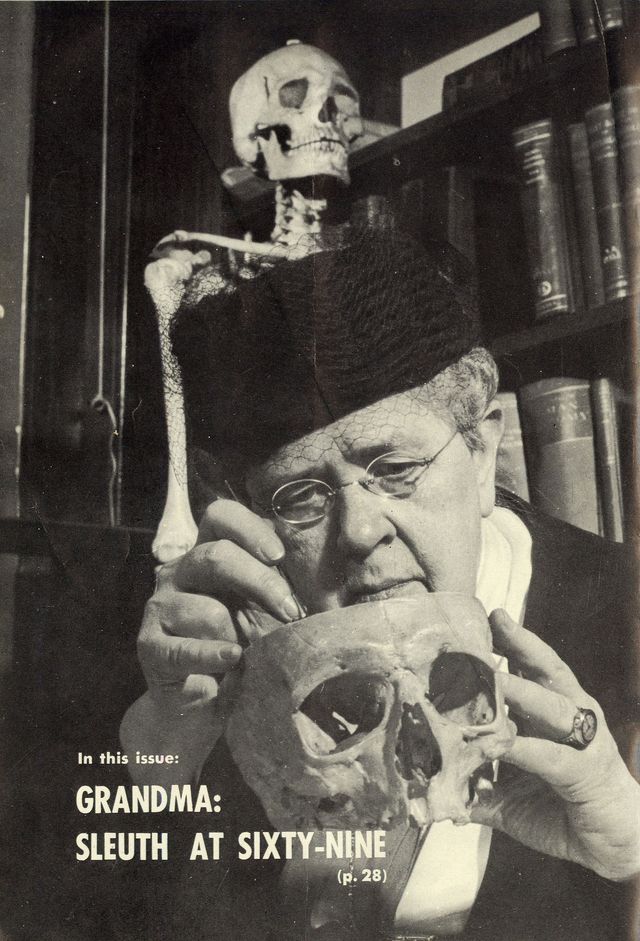

Lee began working with the New Hampshire State Police. In 1943, she was appointed captain, becoming the first woman in America to hold the position.

The legacy of “Forensic Science Godmother”

Through the models Lee created, which were donated to Harvard in 1945, students there could learn how to effectively collect crime scenes to discover and analyze evidence. Through their findings, they can determine whether the scene was the result of a murder or suicide, death by natural causes or an accident.

Lee passed away in 1962, at the age of 84. A few years after her death, Harvard’s Department of Forensic Medicine was dissolved and Lee’s Nutshell paintings were subsequently transferred to the Maryland Office of the Medical Examiner.

There, the paintings still exist and continue to be used as training tools in forensic seminars, attracting more than 100,000 visitors.

In addition, her brief studies of unexplained deaths also inspired television shows, such as “CSI : Crime Scene Investigation.” .

Lee’s legacy continues to this day.